Mary Larson uses her nursing and artistic skills to showcase those touched by homelessness

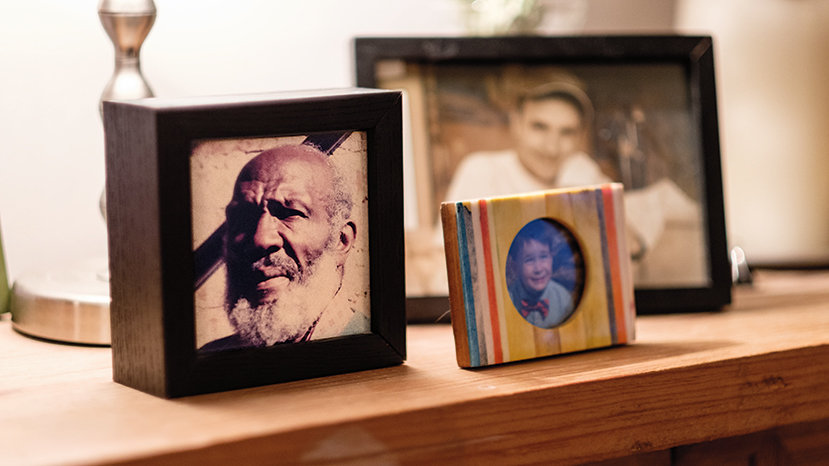

Among Mary Larson’s living-room pictures is a small photo of a man with furrowed eyebrows and a full white beard. His name is James, but when Larson knew him, he was better known as “The Professor.”

The two met in 1995 when Larson was a volunteer nurse at Christ House in Washington, D.C., a medical respite center for the homeless. James was a patient there, tall, quiet and always carrying around a large duffel bag stuffed with sheet music. At lunchtime, he’d sit down at the center’s piano and make it come alive with exquisite music, Larson said.

The Professor, the story went, had once been an instructor at a prestigious college before a life event left him homeless.

“I think his photograph is out with all of our family photos because he will forever be special in my life,” Larson said.

“It’s just a reminder to me that you never know what’s going on in somebody’s life and you never know what can happen in your own life.”

The Professor eventually became one of Larson’s first portrait painting subjects. Larson has become known in the Seattle area and beyond for creating vivid portraits of her patients at Harborview Medical Center’s Pioneer Square Clinic.

All of her portrait subjects have been touched by homelessness, said Larson, who is the clinic’s assistant nurse manager.

The cradle Catholic and parishioner at St. Luke in Shoreline said her faith has taught her “that we are in this life together. And a big part of it is helping each other and doing whatever little thing we can to make our world a better place.”

She added, “I’m hopeful that with my art that’s one of the ways that I am able to try and make it a better place.”

Learning and living Gospel values

Larson grew up in an active Catholic family with a service mentality. Her uncle, Father Jan Larson, is a senior priest for the Archdiocese of Seattle. Her parents were involved at Our Lady of the Lake Parish in North Seattle, and she attended the parish school there before going to Bishop Blanchet High School.

Her Catholic upbringing taught her to incorporate Gospel values into everyday life, she said. A particularly influential experience for her was when Bishop Blanchet’s campus ministry program made cheese sandwiches and took them to the St. Martin de Porres Shelter, which serves homeless men over 50.

“That was one of my first big experiences with homelessness and probably one of the most important in determining my trajectory,” she said.

Around the time Larson was in high school, her family started attending St. James Cathedral, where they got to know Archbishop Raymond G. Hunthausen. Larson said the archbishop emeritus, and his focus on service, is one of her inspirations. (Larson’s portrait of the archbishop hangs in Cathedral Hall today.)

She remembers often reflecting on the cathedral’s skylight, etched around the interior rim with the words “I am in your midst as one who serves.”

Archbishop Hunthausen encouraged Larson to attend his alma mater, Carroll College in Helena, Montana. There she earned a nursing degree and decided to focus on working with the poor and homeless.

But Larson also has been artistic since she was young, doing illustrations, cartoons and eventually photography. In college, she would call home and debate her career path with her parents. “‘Someday you will figure out a way to blend your art with nursing,’” they told her. “And I never believed them.”

During her volunteer year at Christ House in D.C., she used her family’s graduation gift of a camera to take photographs of homeless people like The Professor. After moving back to Seattle in 1996, she started nursing work at the Pioneer Square Clinic and various shelter sites. She’s been full-time at the clinic since 1998.

On a rainy day in Seattle several years after college, Larson passed an art supply store in Fremont, went in and bought some paints to try out. The first paintings she did were portraits based on the photos of homeless people she’d taken in D.C.

After Larson hung some of those portraits in the Pioneer Square Clinic, she’d find her patients staring at them. Without knowing the stories of the portrait subjects, the patients would tell her, “I was homeless once and I can tell that they are homeless.”

Then some of the patients asked her to paint them. She has since completed more than 300 such portraits.

She asks each of her subjects to tell her one thing they want people to know about them and bases the painting’s backdrop on that detail. She often works on a series of portraits all at once. The work goes in stops and starts around her full-time nursing job and life with her husband, Joe Mahar, and their 9-year-old son, Paddy.

A story in every painting

Larson said she wants people to smile when they look at her work. Each subject should invite you in.

There’s Felton, a regular client and a former boxer. He casually grins at the viewer in front of a Wheaties logo, like the cereal box Muhammad Ali once appeared on.

“He has the patience of a saint, he’s been waiting so long for me to finish,” Larson said of Felton’s portrait.

“I think that Felton, like so many people I paint, is a champion. He’s gone through some of life’s most difficult times and still keeps his smile. He still keeps hope and happiness no matter how hard times have gotten. He knows that with this art he’s able to help people by lending his face to this project.”

There’s Marguerite, who lights up her painting with a toothy smile, a Brillo logo behind her representing the time she and her daughter were homeless but made sure to help out at the shelter where they stayed. There’s another James, dapper in a white suit in front of a backdrop of sweet peas, one of his favorite foods. He died last fall before getting to see his finished painting.

There’s Larry, who also recently passed away, slightly squinting at the viewer. The Price is Right logo peeks out behind him — he would skip clinic appointments if that show or Let’s Make a Deal were on TV.

There’s Rufus, who collects recyclables, a Dole banana logo behind him denoting one of the most common boxes he picks up. There’s Matthew, whose love of remote-controlled cars is displayed in his Hot Wheels background.

“Who wouldn’t be honored to have a portrait painted?” said St. James Cathedral’s pastor, Father Michael Ryan. “Usually it’s only the high-end people who commission an important artist to do their portrait. Here’s Mary making these people feel like they are very important.”

Father Ryan has known Larson since she was in college and said she is passionate about her work with the homeless but not “in your face” about it.

Yet her paintings stand out with a bright, bold palette of acrylic on canvas. “I just think painting is fun and I haven’t gone through a dark period yet,” Larson said.

“There’s a certain degree of whimsical in the paintings of the homeless she does,” said her husband, Joe. “She’s trying to let them feel better about themselves, trying to give them a little dignity.”

“When I look at someone’s face, there are just so many interesting things I see in them. A sparkle in someone’s eye, just a joy in their smile, sometimes some sadness,” Larson said.

There are some portraits Larson has a hard time letting go of. The Cowboy is one of them. It hangs in the lobby of the Pioneer Square Clinic. The real-life Cowboy arrived at the clinic dressed in authentic duds. He worked with mules traveling through the Grand Canyon but had come to Seattle for seasonal work that fell through. He lived in a shelter until he could save enough money to return home; he sent Larson photos once he was back in Arizona.

Like The Professor, Larson said, The Cowboy is another example of “There but for fortune, may go you or go I,” citing song lyrics that often run through her head as she hears her patients’ stories.

Bartering for art

When Larson was getting ready to hang her first series of portraits at a Starbucks in Seattle, it didn’t feel right to list them for sale for money. At the same time, the Pioneer Square Clinic was in need of new socks for its clients. So Larson listed the portrait prices as several hundred pairs of socks. They quickly sold, and she has maintained this charitable bartering system for her work ever since.

Paintings have sold for hundreds of cans of food, sandwiches, gloves, hats and other items needed at the clinic, area shelters, food banks and charities. One painting of a man called A.C. sold for top-notch tape measures donated to a Habitat for Humanity site. A newer portrait of a man named Eddie will sell for Starbucks gift cards for the homeless, a request by coffee lover Eddie himself.

Larson recalls how another client once shouted from an exam room at her that it was going to be a cold winter so she needed to paint him and sell the portrait in exchange for warm blankets.

“That’s another thing that makes this art fun for me, working with all these patients to help people,” Larson said. “No matter where we are in our life we are all able to make a difference somehow.”

“It’s really wonderful to see the joy that her paintings give to her patients,” said Dr. Leslie Enzian, an attending physician at the Pioneer Square Clinic. “I think that it gives them a sense of value in this world for patients who often feel completely unvalued in our society.”

Larson has worked with many groups that want to collect donations in exchange for a painting. St. Luke School in Shoreline, where her son attends fourth grade, planned a Catholic Schools Week project this year where the fourth- and eighth-graders teamed up to make sandwiches for a portrait.

Eighth-grade homeroom teacher Rosemary Conroy said that Larson’s slideshow presentation to her class about the project really personalized the homeless for the kids. “Sometimes those are the invisible people in our life,” Conroy said. “she talked about them like they were her dearest friends.”

Northwest Catholic - March 2017