Despite wildfire smoke and COVID-19 limitations, Linda Ellis drove on a September morning to a shared housing building in Seattle.

Waiting for her was a 29-year-old man, Wes, recently released from the state prison in Shelton after four years of incarceration. Ellis never asked about his crime — “an assault of some kind,” she remembers.

Wes began climbing into the back seat. “I’m fine for you to sit up front if we keep our masks on,” Ellis told him, even though it was the first time since March that anyone besides her husband had ridden in the car with her.

Ellis, 74, a longtime member of St. Joseph Parish in Seattle, was driving Wes to an appointment with his community corrections officer, a requirement as he began his life outside the prison walls.

“‘How’s it going for you?’ is the conversation we had,” Ellis recounted. “We talked about what a job would be like. He’s been overwhelmed. It’s a slow process.”

Ellis, a retired high school teacher, met Wes through a ministry called One Parish One Prisoner that has been active at St. Joe’s for about two years. Known as OPOP, the ministry helps parishioners build relationships with soon-to-be-released inmates — via letter-writing, phone calls and prison visits — with the goal of easing their transition back into society.

“It’s like wrapping yourself around someone, just to let them know they’re not alone,” said St. Joseph’s Deacon Steve Wodzanowski.

‘We all have demons’

St. Joseph’s, St. Teresa of Calcutta in Woodinville and Our Lady Star of the Sea in Bremerton are among a dozen churches of different denominations to pilot One Parish One Prisoner.

The ministry was started by Chris Hoke, a Presbyterian pastor and chaplain to gang members and inmates in Skagit County, after he was told the number of inmates in Washington state roughly equaled the number of churches. Hoke, founder of Underground Ministries, didn’t know if that statistic was correct, but he thought pairing parishes and prisoners was a wonderful idea. He’d seen first-hand the difficulty that former inmates experienced re-entering society after serving their time.

Hoke connected with Joe Cotton, director of pastoral care for the Archdiocese of Seattle, a connection that took the One Parish One Prisoner concept from “just some kid working in the basement” to “legitimate,” Hoke said.

Cotton put out the call for local Catholics to participate, initially reaching out to those experienced in prison ministry.

One of those answering the call was St. Teresa of Calcutta parishioner Mark Straley, who describes himself as being in Alcoholics Anonymous since 1992 and, earlier in life in California, spending a decade going to jail “on a regular basis.”

“I never did prison time, but I did jail time, so I’m right at home out there,” Straley said.

He didn’t have to think twice about helping a soon-to-be-released prisoner re-enter society — to Straley, helping those in need is part of the legacy of his parish’s patron saint. “The way I see it, we say ‘Yes’ or we change our name.”

The decision to join the ministry was equally easy at Our Lady Star of the Sea, where parishioner Jim Johnson was already engaged in prison ministry. The parish was matched with Tracy, who Johnson knew from his four years visiting Mission Creek Corrections Center for Women in Belfair. She never missed the Monday and Wednesday evening events, which included eucharistic prayer services, watching movies about saints and discussions about the catechism or living lives of virtue, Johnson said.

“She came to us as a non-Catholic, but she fell in love with what we were doing there,” Johnson said. While incarcerated, Tracy was baptized in 2017 by Auxiliary Bishop Daniel Mueggenborg. Earlier this year, she left prison on a work release program, graduating to ankle monitoring six months later, during the summer of 2020. She immediately began attending Mass at Our Lady Star of the Sea.

“She’s been struggling,” Johnson said in late summer. “She’s reaching out for spiritual guidance.”

Some of Tracy’s family members in the area suffer from addiction, and one of them contacted her on a recent Sunday. “She wasn’t anticipating that,” Johnson said. “We sat with her awhile.”

Everyone has things in their past “that make us not all that different” from former inmates, Johnson said. “We all have demons.”

Transformation, a two-way street

A core group of parishioners at St. Joseph have built relationships with two former inmates — Wes, and before him, Diego.

“From the first time I met him, I thought he was such a lovely, gentle soul,” parishioner Leslie Overland said of Diego, who came to the U.S. as a child, was imprisoned at age 16 and spent 10 years behind bars. “He’s an incredibly smart and curious person. He had a lot of peace. That was just something you could sense about him,” Overland said.

Diego’s situation also educated parishioners about the corrections and immigration systems, which Overland describes as “very broken.” Because Diego’s green card expired while he was in prison, he was slated for deportation immediately after his release.

Cotton, the pastoral care director, remembers visiting Diego when he chose to be deported rather than spend another three to four years in a detention facility fighting to remain in the U.S. He explained to Cotton how the relationship with St. Joseph parishioners affected his life.

“I’ll never forget,” Cotton said. “He was the one who said, ‘I can trust again, and I never thought that was going to happen. Those people have no idea what they have done for me.’”

None of the parishioners who spent time with Diego anticipated deportation as the outcome of their efforts. As Cotton said, “The Gospel is not about storybook endings, it’s about transformation.”

And transformation is a two-way street.

“The parish community will be transformed as much as the person is by the parish,” Cotton said.

Overland agrees. “What starts out as a ministry transitions into a relationship,” she said, “and like anything — whether it’s a new job or a new city or a blind date — it transitions into a relationship where people are benefitting and growing and learning and sharing on both sides of that.”

Walking the talk

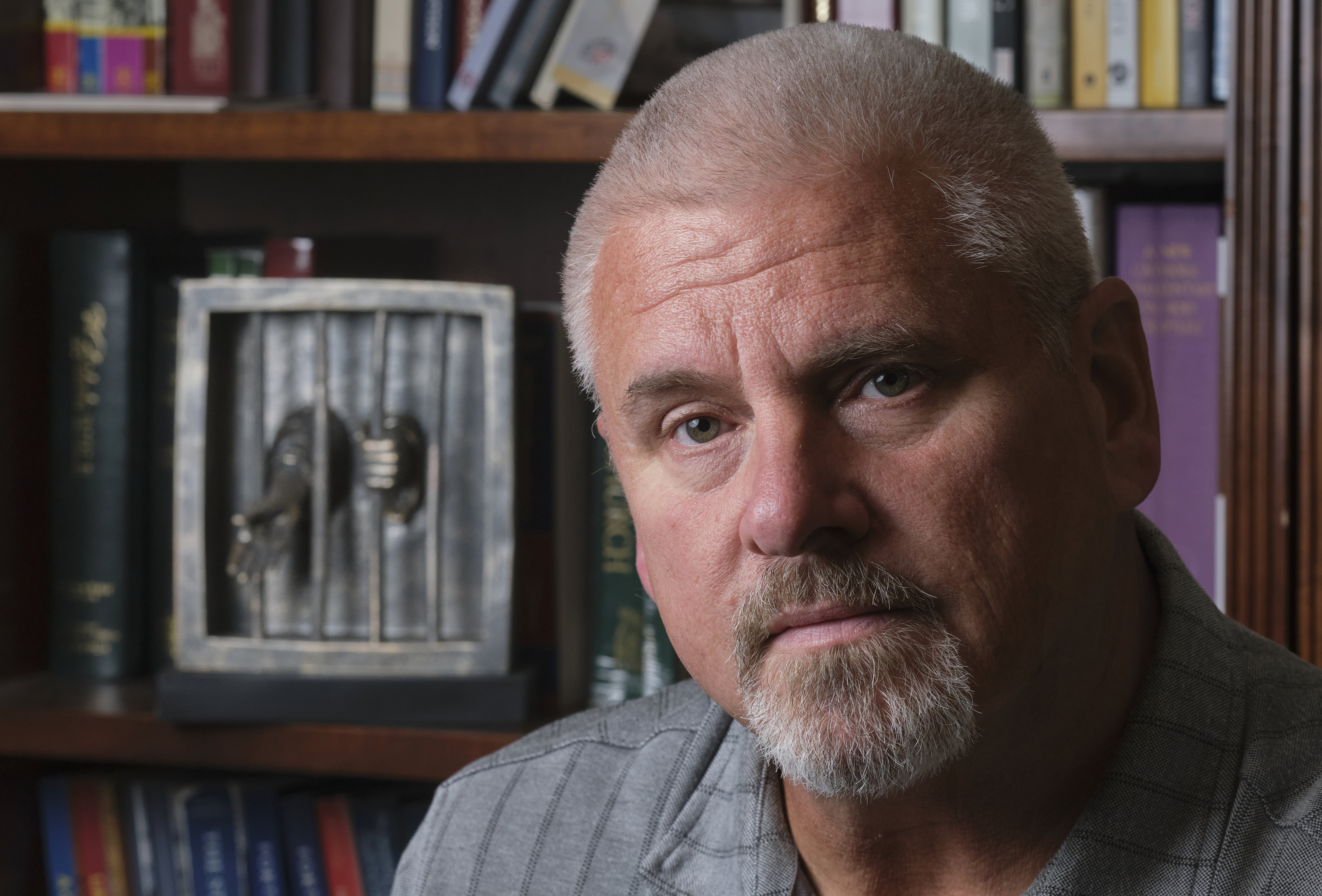

Jim Bloss, a member of St. Mary of the Valley Parish in Monroe, said the mission of OPOP falls directly in line with the Catholic faith.

“If you are a true believer in the seven social justice principles outlined by the [U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops] then you should be taking action,” said Bloss, a military veteran who calls himself a born-again Catholic. “You should be out there putting your feet and hands where your mouth is.”

Bloss, who participates in OPOP with a nearby Presbyterian church, said the decision to engage in the ministry was easy. He already volunteers in prisons through the National Alliance on Mental Illness and knows people who have been in and out of prison. But he understands why other Catholics may hesitate.

“What I’d say is that if you even think you might want to do it, that could be the Holy Spirit moving you in that direction,” Bloss said.

Although OPOP embodies Catholic social teaching, “people haven’t been banging down my door to do this,” Cotton said. “I’d be delighted to have 50 parishes sign up.”

While a small core of people at a parish may engage directly with a former prisoner through OPOP, there are countless other ways to help, such as procuring a laptop, investigating potential jobs or preparing a room at a group living space with bedsheets and towels.

“There are lots of challenges for people when they come out of prison, which is why we have such a high recidivism rate,” said

Overland, the St. Joseph parishioner. “You need a job, but you can’t get a job unless you have an ID, and you can't get an ID until you have an address and a place to live,” she said. “People are sort of just let go and expected to navigate a system they’ve never had to deal with before.”

OPOP seeks to ease that navigation.

“We’re journeying with him,” Linda Ellis said of the parish’s relationship with Wes. “We all want Wes to achieve what he wants, but he’s the prime mover on that. I hope that he can do it.”

One Parish One PrisonerFind out more at undergroundministries.org/opop or contact Joe Cotton, director of pastoral care for the Archdiocese of Seattle, at 206-382-4847 orThis email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. document.getElementById('cloak1fed62a95725491a8ccd2be0382ec8f0').innerHTML = ''; var prefix = 'ma' + 'il' + 'to'; var path = 'hr' + 'ef' + '='; var addy1fed62a95725491a8ccd2be0382ec8f0 = 'joe.cotton' + '@'; addy1fed62a95725491a8ccd2be0382ec8f0 = addy1fed62a95725491a8ccd2be0382ec8f0 + 'seattlearch' + '.' + 'org'; var addy_text1fed62a95725491a8ccd2be0382ec8f0 = 'joe.cotton' + '@' + 'seattlearch' + '.' + 'org';document.getElementById('cloak1fed62a95725491a8ccd2be0382ec8f0').innerHTML += ''+addy_text1fed62a95725491a8ccd2be0382ec8f0+''; .

Northwest Catholic - November 2020