WASHINGTON – The Shroud of Turin is “such a powerful image of God’s love because Jesus willingly underwent this for our salvation,” said Brian Hyland, curator of the Museum of the Bible’s current exhibit on the 14-foot-by-4-foot linen cloth many people believe is Jesus’ burial shroud.

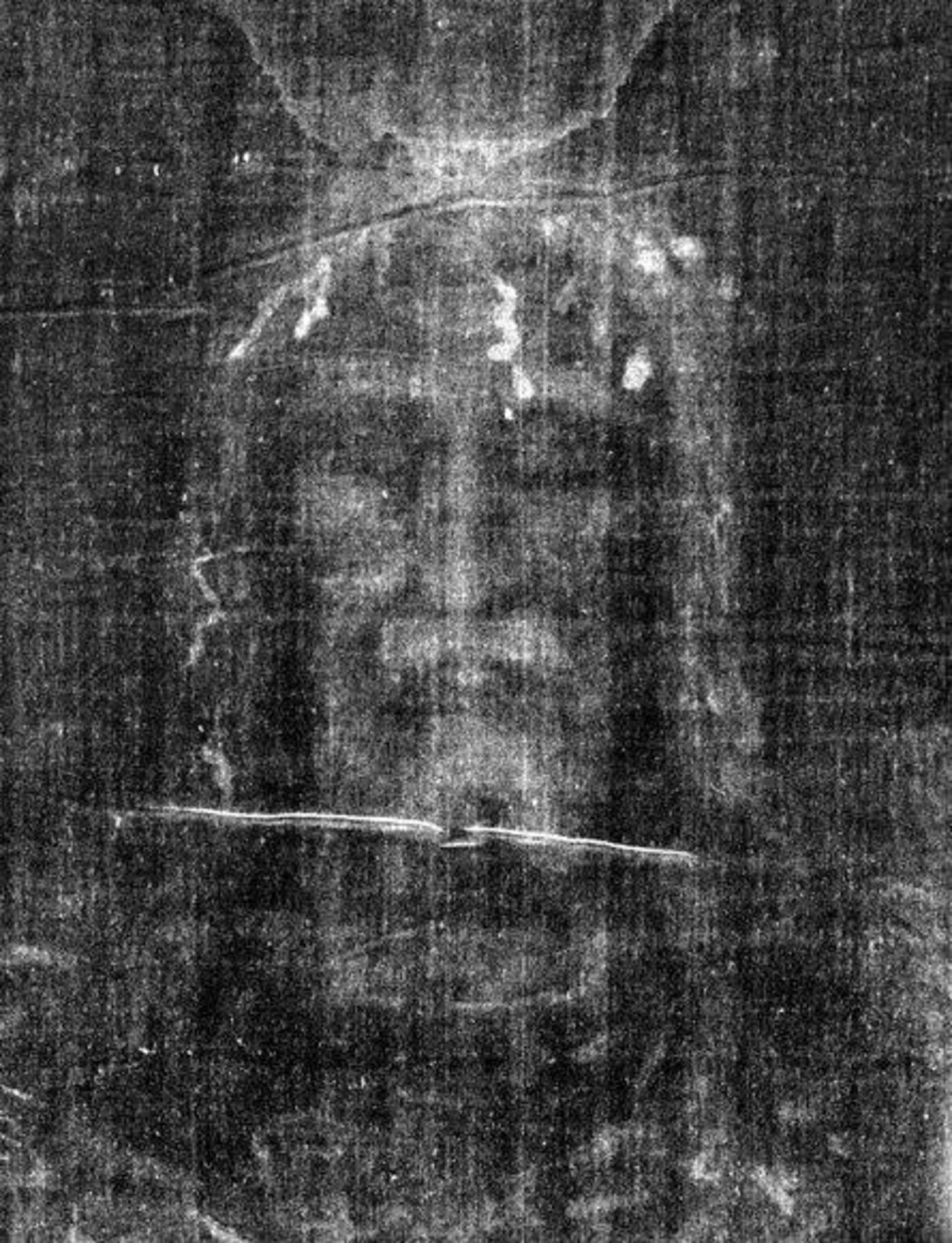

The shroud has a full-length photonegative image of a man, front and back, bearing signs of wounds that correspond to the Gospel accounts of the torture Jesus endured in his passion and death.

Though the artifact itself remains in northern Italy’s Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Turin, the Washington museum’s “Mystery and Faith: The Shroud of Turin” exhibit showcases all — from the shroud’s history and artifacts to interactive activities — to teach visitors about this mysterious phenomenon.

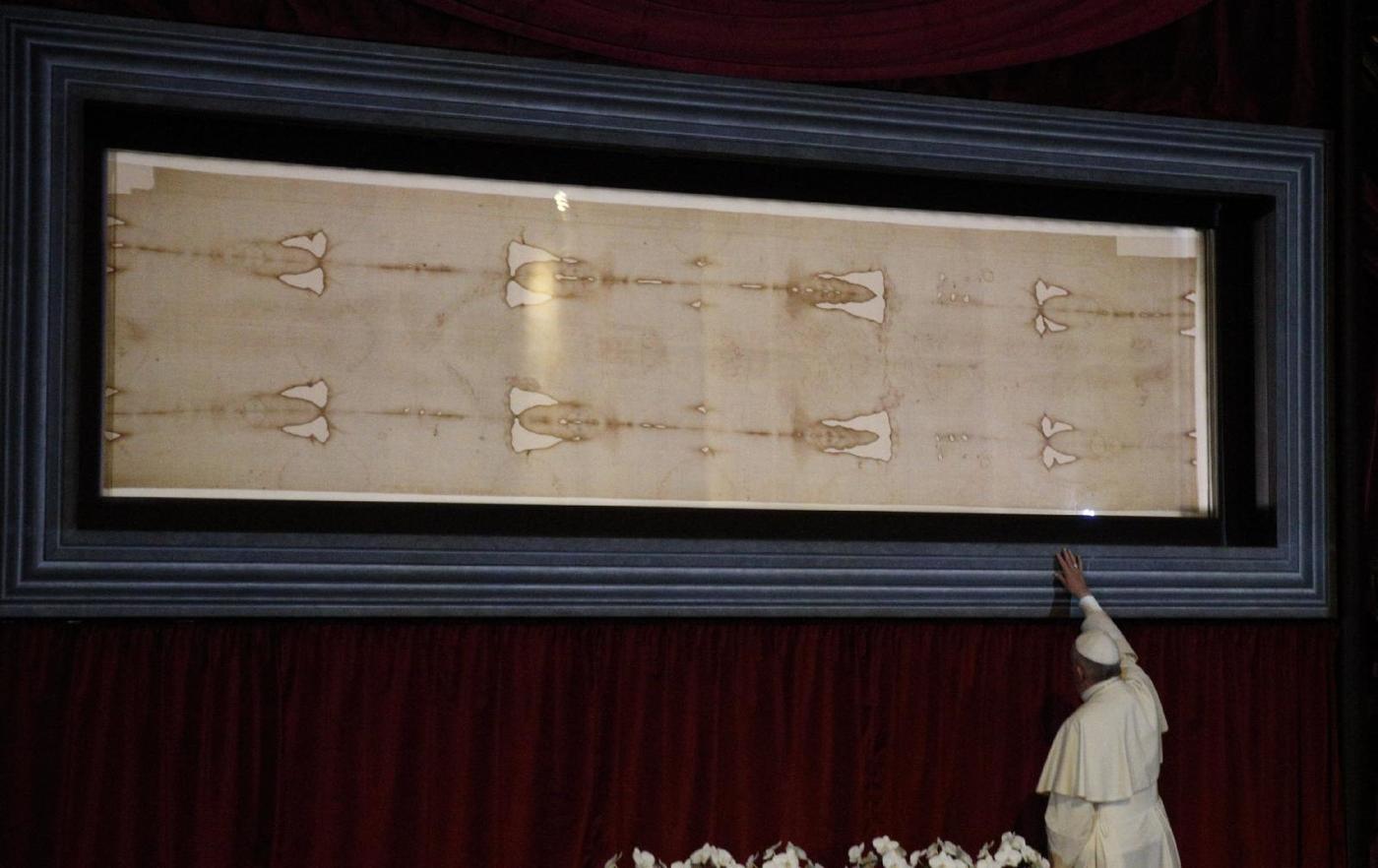

“It is the heart of the exhibit,” Hyland told Catholic News Service. “It doesn’t matter that this is a facsimile. When you look at it through the eyes of faith, that is what you see.”

The Catholic Church has never officially ruled on the shroud’s authenticity, saying judgments about its age and origin belonged to scientific investigation, but recent popes have referred to it as an “icon” of Jesus. Scientists have debated its authenticity for decades, and studies have led to conflicting results.

Right at the Museum of the Bible’s entrance, across from curved doorways and quotes painted on the wall, hangs a life-size copy of the Shroud of Turin.

The linen itself was handmade by a company in Gandino in northeastern Italy. Using heirloom flax plants and ancient weaving patterns, the facsimile was created to mirror the manner in which it would have been woven in earlier centuries. An identical image to that of the real shroud was then printed onto the new linen.

Few would know with the naked eye that it is even different from the real thing, which is kept in a metal case in a chapel in the Turin cathedral and put on public display only occasionally.

The last public exhibition of the shroud was in 2015, but in April 2020 Turin’s Archbishop Cesare Nosiglia led a livestreamed prayer service in front of the shroud as part of a Holy Saturday prayer for an end to the coronavirus pandemic.

Hyland, who also is the museum’s associate curator of medieval manuscripts, used his vast knowledge of history and faith to carefully craft the exhibit to be special and memorable for all. It’s a testimony of the shroud’s impact through history, theology and science — and its significance as a source of curiosity.

“The image in the cloth gives us a great opportunity to allow people, who only have surface knowledge, to want to come and dig deeper,” said Jeff Kloha, the museum’s chief curator.

Before visitors reach the copycat shroud, they will see a table with a representation of the image on the cloth, raised to imitate a body. All over it are sensors, and when activated, a woman’s voice recites a Gospel message that references Jesus and his body during his persecution and crucifixion.

On the wall is a quote from St. John Paul II: “For the believer, what counts above all is that the shroud is a mirror of the Gospel. ... Whoever approaches it is also aware that the shroud does not hold people’s hearts to itself, but turns them to him.”

For Hyland, the pope’s words are a powerful testament as to why it is an icon and source of devotion.

The exhibit’s history section takes the visitor on a journey through the Shroud of Turin’s own expedition through time. It includes the shroud’s locations through time, its effects on historical events, and the circumstances in which it ended up where it is today. There also is a timeline of events that explains what caused distress to the linen, including burns, stains and the removal of entire pieces of it.

The shroud has been in Turin since 1578; the earliest documented evidence of the cloth dates to 1354 when it was deposited in Lirey, France, by a French nobleman who participated in the Christian Crusades to the Holy Land. At the time, the shroud was believed to be the burial cloth of Christ and to have been brought from Constantinople.

In 1453, ownership passed to the House of Savoy and the shroud was moved to Chambrery, France, headquarters of the Savoys, one of Europe’s important noble families. At Chambrery it was damaged by fire in 1532.

The shroud was moved to Turin when the northern Italian city became the center of Savoy family activities. For most of its existence in Turin, it has been kept in the cathedral there.

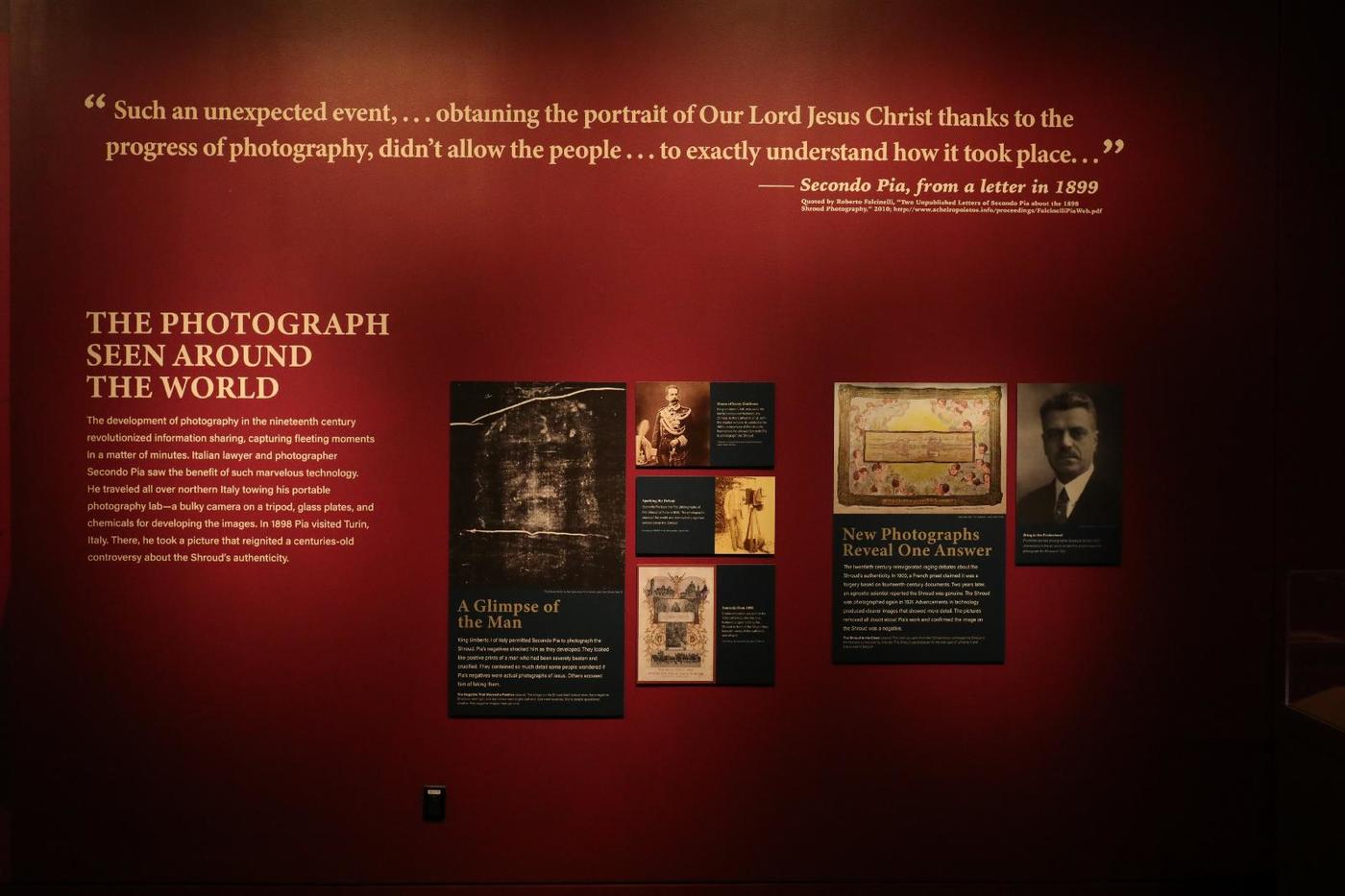

Near the end of the exhibit is a section dedicated to science. Despite the controversy over the shroud’s authenticity, this portion of the exhibit simply explains research done on the shroud.

It was famously photographed for the first time in 1898 by Secundo Pia and his images were met with controversy. When Pia developed his photographic plate, what he found was not a photographic negative, as should have been the case. Instead, he found a positive image, as if the plate had already been printed.

The results of research in the late 20th century led scientists to conclude, through radio-carbon dating, that the linen dates back to when Jesus of Nazareth would have walked the earth.

An interactive activity allows museum visitors to take a photo and see a negative print of the photo.

Hyland and Kloha refer to the shroud as “the first selfie, the first viral image that shows up all around the world!”

In a final section of the exhibit is a wall of artwork that features changing projected images and quotes, including: “Who do you say that I am?” (Mark 8:29). Visitors can write a note in response to questions about what the Shroud of Turin means for them, all hung up on hooks on an opposite wall.

Myra Kahn Adams, one of the founders of SignFromGod.org, was among those who proposed this innovative exhibit. Her mission with the website is to educate people about the Shroud of Turin. She also is executive director of the Sign From God organization.

“Today, four years after the Sign From God board presented our shroud exhibition vision to Dr. Jeff Kloha — three shroud expert speakers’ events later, and a one-year COVID delay — the exhibition is opening along with a potential world war,” she wrote in a column near the February 26 opening of the exhibit. “Could the man of the shroud provide faith, hope and comfort? Perhaps. And is the timing just coincidental?”

“Those without faith,” she added, “should consider why a prestigious museum in Washington, D.C., is hosting an exhibition about what some think is a controversial medieval forgery.”

Whether one is a believer in God or not, the shroud represents many different aspects of faith, culture and history. The final interactive experience is meant to make people think about what they have just observed.

“Come to the exhibit with open eyes and an open heart. I think that is the way, even if you don’t believe that the shroud is real, that it will have a tremendous impact on you,” Hyland advises visitors.