Do you want the Eucharist to change your life? One of the most fruitful ways we can celebrate the Year of the Eucharist as the people of God is to look at the lives of the saints who have gone before us. Seeing how the Eucharist changed their lives offers a pattern for how it can change our lives.

Observing, learning from, and imitating the saints and their devotion to the Eucharist helps us to celebrate the Mass with the “devotion and full collaboration” that the Second Vatican Council promoted in its document on the liturgy.

Archbishop Paul D. Etienne’s pastoral letter The Work of Redemption illustrates this point in its citation of Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical Deus Caritas Est: “The saints … constantly renewed their capacity for love of neighbor from their encounter with the Eucharistic Lord.”

When an apprentice learns a craft, he or she must follow the example of an artisan; in a similar way, if we want to learn to receive the Eucharist in a more profound, life-changing way, then we must follow the example of the saints.

A vital connection

While we can see many qualities of the saints in their relation to the Eucharist — adoration, meditation, reverence, intense desire, joy, etc. — one in particular has always struck me: The saints saw an intimate, vital connection between the Eucharist and the sacrament of reconciliation. It seems that, in the mystery of the divine logic, these sacraments produce the greatest effects and changes in us when they are used in tandem. On the flip side, to neglect receiving one sacrament seems to hinder our receptivity to the other.

Part of the greatest preparation we can make to receive Christ’s body and blood worthily and fruitfully is to experience his forgiveness and healing in confession. I like to think of it this way: If I am full of sin, there is no room for Christ; if I live in darkness, I cannot welcome the light; if I am not reconciled to Christ’s body, the church, from whom I am distanced by sin, then I cannot receive that same body in the Eucharist.

St. Paul made this same point to the first-century Christians in Corinth: “Whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord unworthily will have to answer for the body and blood of the Lord. A person should examine himself, and so eat the bread and drink the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body, eats and drinks judgment on himself” (1 Corinthians 11:27-29).

This leads us to a startling fact: We can sin if we do not receive the Eucharist in the appropriate moral and spiritual state. As many saints and theologians have shown, to receive the Eucharist in a state of mortal sin is itself a mortal sin!

So a basic rule of thumb that the church teaches in the catechism, following the wisdom of the saints, is this: “Anyone who desires to receive Christ in Eucharistic communion must be in the state of grace. Anyone aware of having sinned mortally must not receive communion without having received absolution in the sacrament of penance” (CCC 1415).

What is a mortal sin?

But what does it mean to have sinned mortally? The church supplies three criteria for making that evaluation. First, the action itself must concern something serious or grave. A shorthand way to understand this is to assess how close the action is to breaking one of the Ten Commandments or to exemplifying one of the seven deadly sins (pride, wrath, lust, envy, gluttony, greed, sloth).

Second, we have to know that the action is serious. If there was no possible way for us to know that something was wrong, then our culpability is greatly diminished. However, if we pretend not to know, or go out of our way to ignore what we should understand about right and wrong, then we are not off the hook! It’s hard to imagine that an adult “didn’t know” that murder was wrong, for example.

Third, we have to freely choose to do the serious action. While certain things like fear and psychological issues can hinder our ability to make free choices, the more responsible we are for our actions, the more severe it is to choose sin. As the catechism says, “Sin committed through malice, by deliberate choice of evil, is the gravest” (CCC 1859). In the grand scheme of things, a mortal sin means a choice to have something other than God as the goal, meaning and purpose of our life (what is called “the last end” of our actions). As St. Thomas Aquinas explains, “the deformity of a mortal sin consists in a disorder about the last end.”

If we are not intentional about our own moral and spiritual life as Christians (as evinced and fomented by the practice of confession), then we really have no business with the “source and summit of the whole Christian life” (Lumen Gentium 11) bestowed in the Eucharist. Mortal sin directly opposes the very meaning of the Christian life and being a disciple of Jesus; it causes a “rupture of communion with God. At the same time it damages communion with the Church” (CCC 1440). If we are spiritually and morally ruptured from communion with God, then receiving Communion during the Mass is lying about our own identity.

Don’t be afraid!

But, thanks be to God, our Lord Jesus Christ instituted the sacrament of reconciliation precisely to heal this rupture with God and the church. It is by going to confession that we are welcomed back into communion and rendered capable of receiving eucharistic Communion in truth.

If we have committed a mortal sin, we need to go to confession before receiving Communion. The same applies if we haven’t been to confession in over a year. One of the five basic precepts of the church (the “very necessary minimum in the spirit of prayer and moral effort, in the growth in love of God and neighbor” (CCC 2041)) is to go to confession at least once a year. If we have committed venial (lesser) sins, it is a very healthy and holy practice to confess our sins before receiving Communion.

Don’t be afraid to come to confession! Good and holy priests love offering this beautiful sacrament and are always eager to welcome everyone with kindness, compassion and an abundance of God’s mercy. There are numerous times and places available for confession throughout the archdiocese, even during the pandemic!

Look to the saints

It should be clear by now that confession and Communion go hand in hand. But don’t take my word for it! We can look to the saints to draw this conclusion.

St. Catherine of Siena, a doctor of the church who lived during the 14th century, was known for her ecstatic contemplation in the presence of the Eucharist. She was famous for remaining rapt in prayer for hours after receiving the body of Christ; and in those times of intimacy with the Lord, she gained a wisdom more profound than any learned theologians of her era. From this deep union with Christ, St. Catherine taught in her Dialogues that “anyone who would approach this gracious Sacrament while guilty of deadly sin would receive no grace from it.”

St. Charles Borromeo was a gifted bishop given the daunting task of shepherding the church in Milan in the 16th century and implementing the reforms of the Council of Trent.

He drew strength from meditating on the wonders of the Eucharist. Among the many important teachings he passed on to his diocese was this: “The Sacrament of Confession is the first and necessary disposition for the Eucharist.”

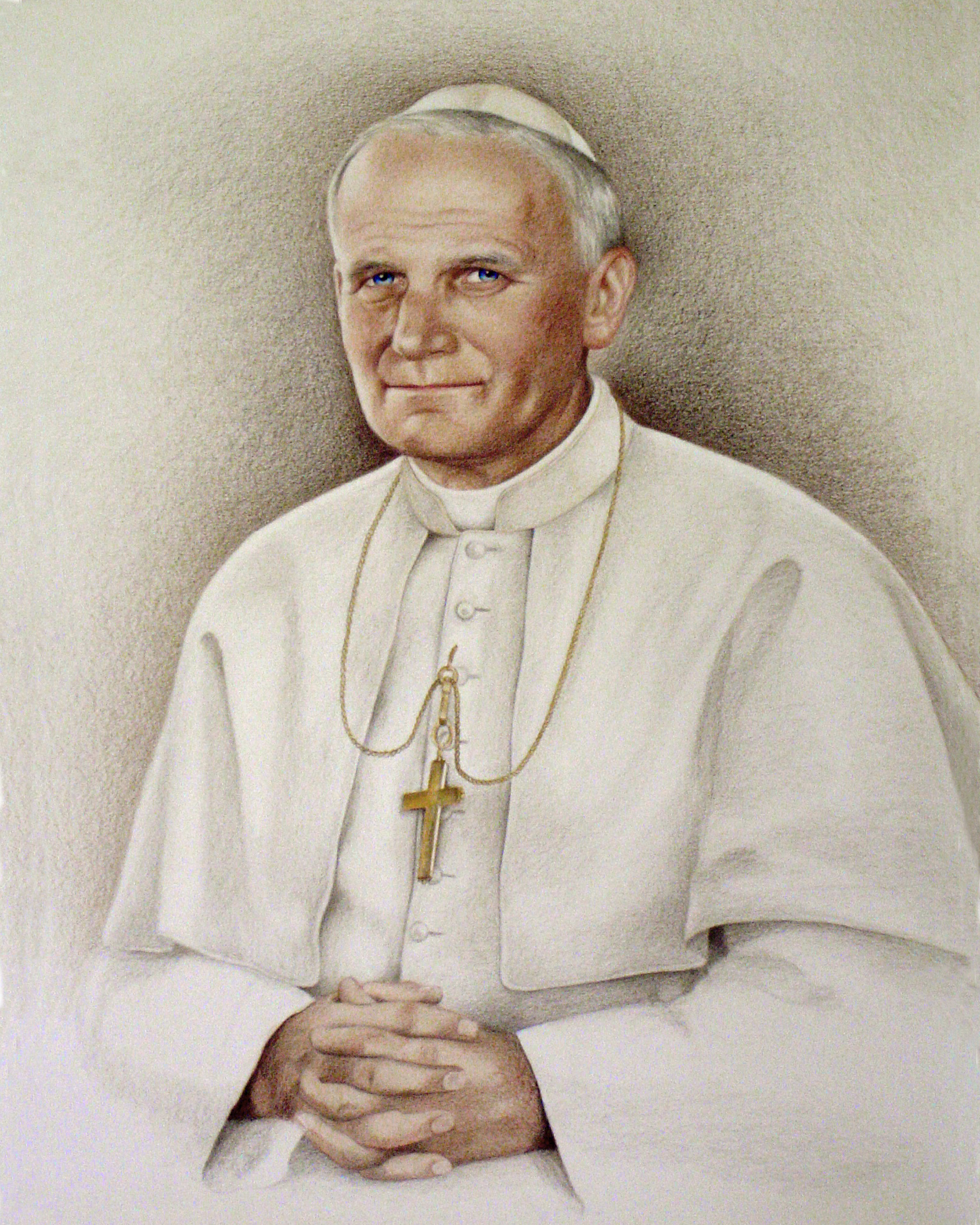

St. John Paul II, whom many of us recall, was pope from 1978 to 2005. He made a great effort to help the church draw ever more deeply from the Eucharist following the summons of Vatican II. In his encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia, he wrote, “If a Christian’s conscience is burdened by serious sin, then the path of penance through the sacrament of Reconciliation becomes necessary for full participation in the Eucharistic Sacrifice.”

What graces flow!

There is a twofold challenge in this teaching from the saints who have gone before us. First, we should not receive the Eucharist from rote habit; just because we are physically present at Mass doesn’t mean we should receive the Eucharist. Rather, we should be very clear about our moral and spiritual state and about why we are at Mass in the first place. Full participation, which is characterized by being “conscious of what [we] are doing” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 48) and by our intentional discipleship in our daily lives, is the prerequisite to a fruitful, life-changing encounter with the Eucharistic Lord.

The second challenge is not to judge those who do not receive the Eucharist. When someone humbly refrains from going to Communion or simply asks a blessing from the priest, we should not start wondering, What did they do? Why aren’t they receiving? Keep your mind on your own soul! Do not look down on or presume to judge others at the very moment when you are called to be filled with divine charity!

What graces flow when a faithful Christian celebrates confession and Communion together! They are like two wings on which we rise up to the love of God. Confession heals, Communion nourishes; the one restores, the other strengthens; the one humbles, the other exalts; God seeks us in one, God embraces us in the other. How noble is the Christian who admits their sin to God with compunction and honesty; how beautiful is the Christian who receives Christ’s body in spirit and truth!

In the saints who have gone before us, we see the experts of the Eucharist. We see men and women who recognized the unbreakable bond between the Eucharist and reconciliation. We see the brothers and sisters who, if we imitate and learn from them, will lend us the wisdom and courage to “run as victors in the race before us and win with them the imperishable crown of glory” (Preface I of Saints).

Dominican Father Thomas Aquinas Pickett is parochial vicar at Blessed Sacrament Parish in Seattle.

Northwest Catholic – January/February 2021